Myanmar is ready to engage mHealth applications for improved postoperative care

Sariah Khormaee MD PhD1, Athena Nguyen2, Esther Bartlett3, Michael Lwin4, Peter Chang MD5, Misja Ilcisin6

1Hospital for Special Surgery, Orthopedic Surgery

2Santa Clara University College of Arts and Sciences

3Santa Clara University College of Arts and Sciences

4KoeKoe Tech Co., Ltd

5Washington University, Orthopaedic Surgery

6KoeKoe Tech Co., Ltd

Corresponding author: sariah.khormaee@gmail.com

Journal MTM 8:1:29–36, 2019

Background: There is incredible potential for telemedicine to advance postoperative care. Work in high-income nations shows the potential to use mobile phones to monitor postoperative recovery progress. However, there is little information about the attitudes of people in low resource countries, like Myanmar, toward the adoption of mHealth in postoperative care.

Aims: This study presents survey results collected in Myanmar to better understand cultural attitudes of this population towards adopting mHealth technologies to improve postoperative patient care.

Methods: A thirteen-question survey was developed, focused on demographic questions and attitudes towards physicians, the internet, and willingness to perform tasks on their mobile phones. Respondents were selected in a sample of convenience in urban and rural public spaces.

Results: Of the 125 people approached, 112 agreed to participate in the survey. A wide range of ages (18-78), genders (55.4% female), locations (22.3% rural, 77.7% urban) and ethnicities (67% Burmese) were represented. 85.7% were willing to make contact with a surgeon in a hypothetical postoperative setting via mobile phone. 83.0% were willing to fill out a survey about their postoperative state and 69.6% were willing to send a picture of their wound with their surgeon via mobile phone. A majority of respondents had a very high level of trust in physicians in general, most already owned a mobile phone with access to the internet and used it to look up health information.

Conclusion: Our results indicate that Myanmar could provide a promising location for the implementation of mHealth technologies to improve post-operative care.

Keywords: mobile health, telecare, health information on the Web, ehealth, assistive technologies

Introduction:

The role of mobile technology to augment and improve postoperative care is immense.1,2,3 Mobile health applications offer promising avenues for physicians and patients to exchange critical health information for improved convenience, cost reduction and efficiency. This is particularly valuable in the developing world, where such increases could greatly affect access to care, patient outcomes and management of complications.4,5 Thus far, mobile health (mHealth) applications in low resource countries like Myanmar have focused mainly on primary care, maternal health and management of chronic diseases.4,6,7 However, developing new mHealth applications for postoperative monitoring of patients could have a major impact.8,9,10 This technology could enable early identification of complications and aid in efficiently evaluating overall patient outcomes which would ultimately decrease length of hospital stay and facilitate patient recovery.8,9,10

Emerging work in Western and developed nations is beginning to show widespread patient support for using mobile phones to monitor postoperative recovery.11,12,13,14,15 For instance, Abelson et al. recently found in a population based survey of New York State residents that 60-70% of patients were willing or very willing to fill out surveys and send pictures by mobile phones in order to document their postoperative course to physicians.16 Likewise, multiple investigators have revealed enthusiasm in public and patient populations for using mHealth applications to augment postoperative care.17,18 However, investigations have also documented some hesitancy to use mobile phones to convey medical information to physicians due to lack of privacy, familiarity and/or access to technology.19,20

There are significant differences in the delivery of postoperative care in Western and developing countries, including Myanmar.21,22 Care is often limited by scarce resources and a limited medical workforce.21 Patients often live long distances from health care facilities, particularly if their conditions require advanced surgical procedures.23 In addition, there may be unexplored cultural differences that influence the attitudes of patients in Myanmar towards both sharing information and their overall relationships with their healthcare providers.24,25

The use of mHealth to enhance postoperative healthcare delivery in Myanmar offers great potential in alleviating some of these obstacles. Despite the relatively low per capital GDP, the penetrance of mobile phones, especially internet enabled phones, is high in Myanmar- 92.7% of urban households and 65.9% of rural households own a mobile telephone.23 However, there are no studies about the willingness and general attitudes of people in Myanmar to use mobile phones for communicating with their physicians and medical professionals. Here, we present survey results taken in Myanmar to better understand the cultural attitudes and willingness of this population towards adopting mHealth technologies to improve postoperative patient care.

Methods

Survey development

Drawing from prior surveys performed in other populations, a thirteen question survey was developed. 16,18 Seven of the questions seek to obtain patient demographic and background information in order to form a frame of reference and better understanding of the participant. Two questions evaluate the individual overall trust of physicians in general, and whether or not the internet is a major source for obtaining medical information. Four questions related to a theoretical situation whereby individuals are questioned about their willingness to perform multiple tasks on their mobile phones if they were to undergo surgery in the future.

The survey questions were first reviewed by two Myanmar natives to ensure cultural sensitivity and clarity. The full survey is available in the Supplementary Materials. All non-demographic questions have closed-ended answers, although extraneous information volunteered by participants during explaining their answers was also recorded.

Sampling

The survey was translated into Burmese and administered orally to individuals in busy public areas throughout Myanmar in July 2017. Eligibility included all volunteers agreeing to participate who were at least 18 years old or older, and without prior knowledge of their surgical history. Before administering the survey, it was explained to the participants that the purpose of this survey was to better understand how people in Myanmar use mobile phones to communicate their medical needs to healthcare providers.

After agreeing to participate, the survey was administered to each subject by a native Burmese speaker, and the answers were then translated in real time to English for data recording. Out of consideration for the subject’s cultural comfort level, audio recordings were not made of their responses. None of the subjects agreeing to participate declined to either complete the survey or to answer any of the survey questions, so there were no missing responses. The complete administration of each survey took approximately 2-3 minutes per participant.

Of note, although we asked survey respondents specifically about their ethnicity, the concept on ethnicity for those in Myanmar is often conflated with their religious identity, thus, many responded with religious identifiers when asked about their ethnic background, although this does not represent true ethnicity. We reported here what respondents stated when asked about their ethnicity and did not attempt to correct/clarify if respondents answered with a religion when asked about ethnicity.

Analysis

The primary outcome of our survey was to determine if respondents wished to have their physician contact them after surgery. Secondary outcomes included information about patients’ current trust in their physicians and current engagement with online sources for health information. We also collected information regarding patient to participate in mobile health applications in a theoretical postoperative scenario. Although not part of the original survey design, we also made notes of comments by patients who spontaneously volunteered information while taking the survey, to better understand the motivation for their answers. None of the respondents refused to answer any questions, so there were no missing responses.

Microsoft Excel and R v3.4.1 were used for data analysis. P values were calculated for continuous variables with students t test. For categorical variables, the Fisher’s test was used for cell sizes <5, otherwise the Chi test was used.

Results

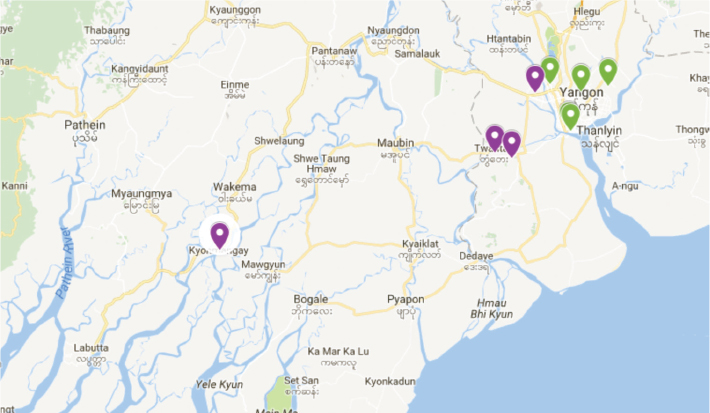

Of the 125 people asked to participate in the survey, 112 (89.6%) agreed to participate. The average age of respondents was 36.6 years (standard deviation 16.7 years, with a minimum age of 18 and maximum age of 78). Of the respondents, 55.4% were female. 77.7% of survey respondents were from urban areas and 22.3% were from rural areas. A map of the survey locations around Myanmar is included in Figure 1. Individuals came from a range of self-identified religious/ethnic groups and professions (Table 1). The majority of respondents, 67.0%, identified as Burmese (Bamar). The next most common self-identified religious/ethnic groups were Muslim (6.3%), Chinese (4.5%) and Karen (3.8%). The most common occupations were sales (20.5%) and other non-manual labor requiring less than a university degree (21.4%). 12.5% of respondents were retired, 11.6% worked at home and 3.8% were unemployed.

Figure 1: Location of survey administration throughout Myanmar with purple icons representing rural areas and green icons representing urban areas.

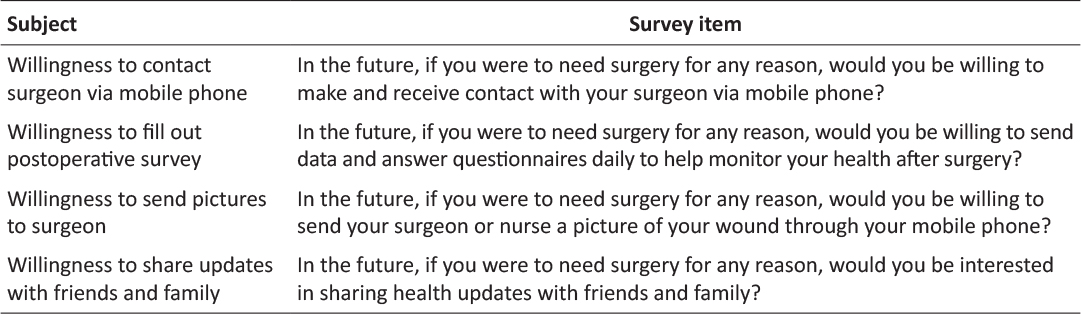

Table 1: Attitudes towards mHealth postoperative care survey questions.

In terms of their medical background, the majority (67.0%) had no surgical history. However, of the 33.0% with a prior surgical history, the majority (81.1%) had some sort of follow-up care).

Mobile phone with internet capability was widespread in our sample population, with most people (90.2%) owning their own phone, which included a phone owned jointly by their families. 88.1% of these phones had internet capabilities. In the population of respondents who owned phones without internet capabilities, most respondents (83.3%) reported that they primarily used their phones to contact friends and family. In those with internet capabilities to their mobile phones, the most common primary usage of their mobile phones was for Facebook (48.3%), calling friends and family (24.7%) and work-related applications (13.5%). Only 25% of respondent reported any contact of any kind with a physician on their mobile phone.

Most respondents (61.2%) had used internet resources in some form to look up health information. Of those that did look up online information about their health, 50.7%, trusted this information “a little”, 44.9% trusted this information “a lot” and 7.7% did not trust the information. This contrasted with respondents’ trust for physicians, which was almost uniformly qualitatively assessed as “a lot” for 84.8% of people, and 13.4% trusted physicians “a little”. Only 1.8% of respondents reported that they did not trust physicians.

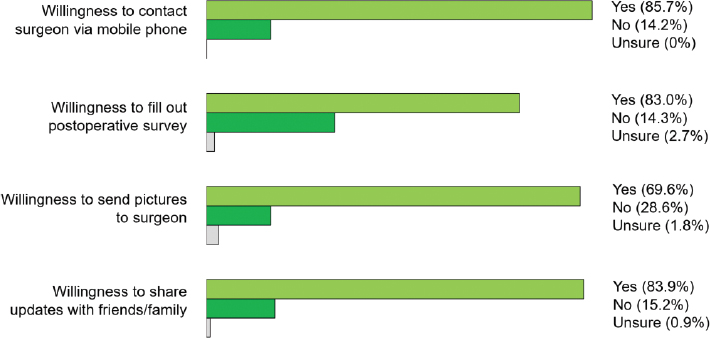

Most were very open with their health information, with 83.9% noting a willingness to share their health information with friends and family (Figure 2). A willingness to share their health information was not associated with gender, age or ownership of a mobile phone, as seen in Table 3.

Figure 2: Attitudes of people in Myanmar regarding engagement with mHealth for various aspects of postoperative care.

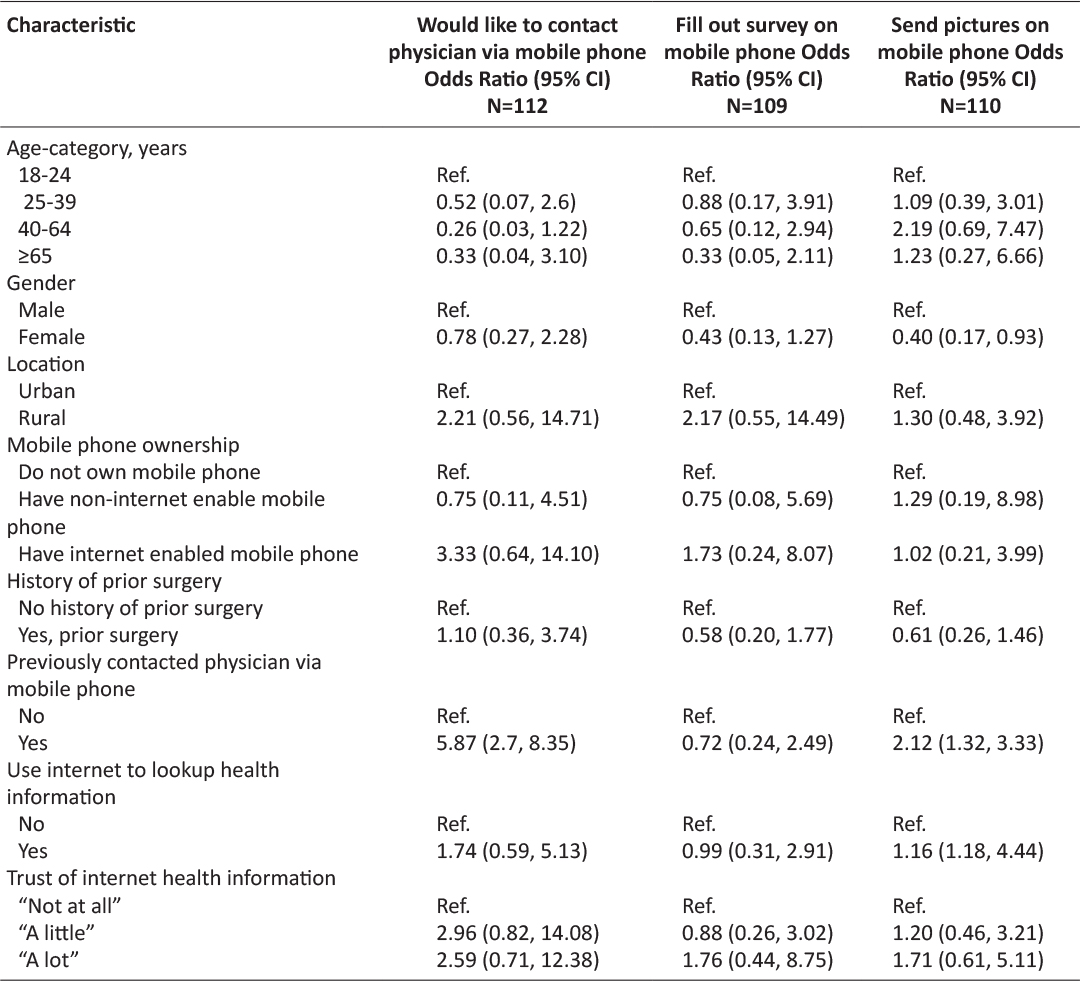

The majority of respondents, 85.7%, expressed a desire for physicians to contact then via mobile phone for postoperative care, irrespective of whether they had previously used mobile phone technology to interface with their physicians (Figure 2). Of note, even in people who did not own a phone, 72.2% were in favor of the theoretical idea of being contacted by phone by their physicians. When presented with a theoretical situation in which they required post-operative monitoring, a majority of respondents, 83.0%, stated that they would be willing to fill out regular surveys to provide information about their recovery to their surgeon. Relatively fewer people, although still a majority at 69.6% were willing to send a picture of their wound to their surgeon. The only variable associated with a decreased wiliness to send a picture of a postsurgical wound via mobile phone to a surgeon was female gender, with an odds ratio of 0.40 when using male gender as a reference, 95% confidence interval (0.48, 0.93).

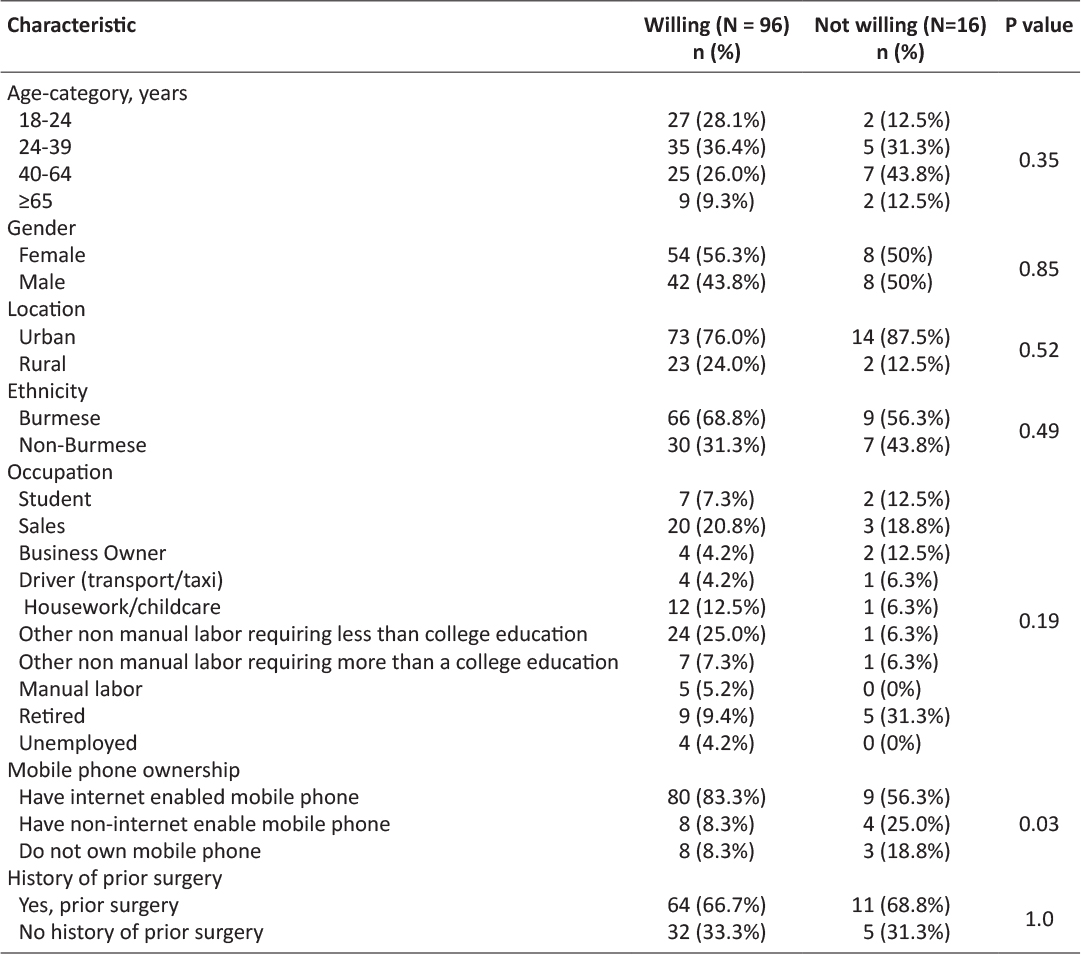

People who had previously contacted a physician with their mobile phone, were more likely to wish to contact a surgeon for postoperative care and send a picture of their wound to their surgeon, as seen in Table 3. Otherwise, there were no significant predictors for increased wiliness in the aspect of mHealth we inquired about. A majority of patients were open to contacting their surgeon via mobile phone in a hypothetical postoperative setting, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, mobile phone ownership, prior contact with a physician via mobile phone and mobile phone ownership (Table 2).

Table 2: Demographics of survey respondents and wiliness to make contact with a surgeon via mobile phone in a hypothetical future postsurgical care scenario.

Table 3: Univariate analysis for wiliness to engage in various aspects of mHealth postoperative care by user status by respondent demographics. Three patients were unsure if they would fill out a survey about their postoperative state and two patients were unsure if they would be willing to send their surgical team a picture of their postoperative wound via mobile phone. These patients were removed from the univariate analysis for these outcomes.

Some qualitative information was collected from patients as a majority of respondents did not restrict their answers to single word responses, but instead preferred to elaborate responses at length. Many favored contact with their physician via mobile phone, but only if this was in addition to seeing their physicians in person, and especially in cases of postoperative monitoring. Some expressed a willingness to fill out questionnaires and take pictures of their wound, but only if requested by their physician.

The most frequent reason cited by participants for their unwillingness to share information with a physician via mobile phone in a theoretical setting was their concern about eroding the patient-physician relationship. Almost all patients who felt that they would not like to contact their surgeons in the postoperative setting cited this as the reason. A majority felt that it was easier for physicians to acquire information and review their condition more thoroughly in-person as compared to by phone. In several cases, respondents stated that their physicians were relatively available, so they did not see the need for mobile phone communication as a significant convenience factor. A few individuals expressed hesitancy to use mobile phones for privacy reasons, particularly with regard to sending pictures of injuries of certain body parts, but would be willing to send photos of “non sensitive” areas. Finally, one respondent felt that mobile phone contact with physicians would only increase physician workload, thus, it would be best to handle all medical needs in person.

Conclusion/Discussion

The potential of mobile phone technology to increase the efficiency and availability of postoperative care in Myanmar is vast. Our survey results suggest that many in Myanmar are receptive to adopting mobile health technologies, with over 85% reporting that they would like their physician to contact them via phone in a hypothetical postoperative situation. Furthermore, based on a theoretical survey question, a majority would be willing to supply regular postoperative information via surveys and provide pictures of postoperative wounds to their healthcare providers. Both patients with prior surgeries and those with no history of surgery showed similar willingness to engage in postoperative mHealth. The application of mHealth technology in developing nations such as Myanmar has the potential to aid in early identification of postoperative complications, promote continuity of care, and allow for better assessment of overall patient outcomes.

Our survey results also shed interesting light on the culture of patient-physician relationships and mobile phone usage in Myanmar. An overwhelming majority of respondents had a high level of trust for physicians, and many patients used the internet to search for healthcare information. This highlights the need to engage patients with trusted medical providers and curate accurate internet sources in Burmese for health related topics.

There were some limitations of our results and methods. First, despite an effort to include both rural and urban respondents, the majority of patients came from Yangon, one of the most highly educated and wealthy cities in the country. It was also a survey of convenience of people in public areas, without the advantages of random administration, so there is likely selection bias towards people with more familiarity with mobile phones and higher health literacy. Thus, we would expect that our survey respondents would be more familiar with the concept of physician contact through their phone as compared to more remote, low income populations in rural communities. In the future, we would like to specifically investigate the more remote areas of Myanmar, since these people might potentially benefit the most from advancements in mHealth.

Overall, the results of this survey indicate that many in Myanmar are enthusiastic about mHealth in the postoperative care setting. However, this survey indicates that successful adoption of mobile phone applications will rely heavily on understanding and strengthening the physician-patient relationship, given the high regard for patients have for their physicians. As in other countries, people in Myanmar show a wiliness to answer survey questions about their health and send in pictures of their wound in a postoperative care setting. Our results support a bright future for mHealth for postoperative monitoring in Myanmar to improve access to health information and physicians.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

References

1. Pathak, A., Sharma, S., Sharma, M., Mahadik, V. K. & Lundborg, C. S. Feasibility of a Mobile Phone-Based Surveillance for Surgical Site Infections in Rural India. Telemed. J. E-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 21, 946–949 (2015). ![]()

2. Cook, D. J. et al. Patient engagement and reported outcomes in surgical recovery: effectiveness of an e-health platform. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 217, 648–655 (2013). ![]()

3. Fernandes-Taylor, S. et al. Feasibility of Implementing a Patient-Centered Postoperative Wound Monitoring Program Using Smartphone Images: A Pilot Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 6, e26 (2017). ![]()

4. Goel, S., Bhatnagar, N., Sharma, D. & Singh, A. Bridging the Human Resource Gap in Primary Health Care Delivery Systems of Developing Countries With mHealth: Narrative Literature Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 1, e25 (2013). ![]()

5. Zanaboni, P. & Wootton, R. Adoption of telemedicine: from pilot stage to routine delivery. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 12, (2012). ![]()

6. Kaewkungwal, J. et al. Application of Mobile Technology for Improving Expanded Program on Immunization Among Highland Minority and Stateless Populations in Northern Thailand Border. JMIR MHealth UHealth 3, e4 (2015). ![]()

7. Hmone, M. P., Li, M., Alam, A. & Dibley, M. J. Mobile Phone Short Messages to Improve Exclusive Breastfeeding and Reduce Adverse Infant Feeding Practices: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial in Yangon, Myanmar. JMIR Res. Protoc. 6, e126 (2017). ![]()

8. Segura-Sampedro, J. J. et al. Feasibility and safety of surgical wound remote follow-up by smart phone in appendectomy: A pilot study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2012 21, 58–62 (2017). ![]()

9. Cleeland, C. S. et al. Automated symptom alerts reduce postoperative symptom severity after cancer surgery: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 29, 994–1000 (2011). ![]()

10. van der Meij, E., Anema, J. R., Otten, R. H. J., Huirne, J. A. F. & Schaafsma, F. G. The Effect of Perioperative E-Health Interventions on the Postoperative Course: A Systematic Review of Randomised and Non-Randomised Controlled Trials. PLOS ONE 11, e0158612 (2016). ![]()

11. Calderón, T. A. et al. Understanding potential uptake of a proposed mHealth program to support caregiver home management of childhood illness in a resource-poor setting: a qualitative evaluation. mHealth 3, 19–19 (2017). ![]()

12. Duplaga, M. The acceptance of e-health solutions among patients with chronic respiratory conditions. Telemed. J. E-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 19, 683–691 (2013). ![]()

13. Russo, L. et al. What drives attitude towards telemedicine among families of pediatric patients? A survey. BMC Pediatr. 17, (2017). ![]()

14. Stypulkowski, K., Uppaluri, S. & Waisbren, S. Telemedicine for postoperative visits at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center. Results of a needs assessment study. Minn. Med. 98, 34–36 (2015).

15. Vesterby, M. S. et al. Telemedicine support shortens length of stay after fast-track hip replacement: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Orthop. 88, 41–47 (2017). ![]()

16. Abelson, J. S., Symer, M., Peters, A., Charlson, M. & Yeo, H. Mobile health apps and recovery after surgery: What are patients willing to do? Am. J. Surg. (2017). doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.009 ![]()

17. Sanger, P. C. et al. Patient Perspectives on Post-Discharge Surgical Site Infections: Towards a Patient-Centered Mobile Health Solution. PLoS ONE 9, e114016 (2014). ![]()

18. Wiseman, J. T. et al. Conceptualizing smartphone use in outpatient wound assessment: patients’ and caregivers’ willingness to use technology. J. Surg. Res. 198, 245–251 (2015). ![]()

19. Atienza, A. A. et al. Consumer Attitudes and Perceptions on mHealth Privacy and Security: Findings From a Mixed-Methods Study. J. Health Commun. 20, 673–679 (2015). ![]()

20. Kotz, D., Gunter, C. A., Kumar, S. & Weiner, J. P. Privacy and Security in Mobile Health: A Research Agenda. Computer 49, 22–30 (2016). ![]()

21. Saw, Y. et al. Taking stock of Myanmar’s progress toward the health-related Millennium Development Goals: current roadblocks, paths ahead. Int. J. Equity Health 12, 78 (2013). ![]()

22. Latt, N. N. et al. Healthcare in Myanmar. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 78, 123–134 (2016).

23. Ministry of Health and Sports – MoHS/Myanmar & ICF. Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey 2015-16. (MoHS and ICF, 2017).

24. Shannon, P. J. Refugees’ advice to physicians: how to ask about mental health. Fam. Pract. 31, 462–466 (2014). ![]()

25. Oleson, H. E., Chute, S., O’Fallon, A. & Sherwood, N. E. Health and healing: traditional medicine and the Karen experience. J. Cult. Divers. 19, 44–49 (2012).