Mobile Technology Usage by Orthopaedic Surgeons and Trainees in Australia

Dr James Churchill MBBS1

1Dept. of Orthopaedics, Western Health, Melbourne, Australia

Corresponding Author: churchie11@gmail.com

Journal MTM 1:2:11-15, 2012

http://dx.doi.org/10.7309/jmtm.12

Background: The use of smartphones and portable tablet devices is increasingly more common and widespread in Australia. Usage amongst medical professionals is increasing in a number of fields. The purpose of this study was to gain insight into the current and future usage of these devices by orthopaedic surgeons and orthopaedic trainees, in addition to understanding the perceived impact on patient care.

Methods: A survey examining mobile technology usage was administered via email to a number of orthopaedic surgeons and trainees across Australia. Data regarding the respondents’ownership and usage of mobile technology, perceived future usage, and impact on patient care and productivity was collected and analysed.

Results: 97.7% of respondents currently use a smartphone, and 58.1% use a tablet device. The most common work use was for professional contact (78%), viewing journals,online educational resources (68.3%), and viewing radiology (46.3%). Respondents showed a significant interest in the ability to view x-rays and computed tomography (CT) in the future. Overall, surgeons indicated that mobile technology improves patient care and productivity, and they believe they will use it more often in the future.

Conclusion: Mobile technology usage is highly prevalent amongst orthopaedic surgeons and trainees in Australia. These technologies may be used to facilitate improved quality and timely provision of care.

Introduction

Mobile technology usage, particularly the use of smartphones and tablets, has increased greatly amongst the general public in Australia in recent years1Petrovic D. Smartphone Usage in Australia. Petrovic D. Smartphone Usage in Australia. cited 2012 Mar. 20.,2Moses A. Australia's white hot smartphone revolution. smh.com.au. 2011 -cited 2012 Mar. 12. Available from: http://www.smh.com.au/digital-life/mobiles/australias-white-hot-smartphone-revolution-20110908-1jz3k.html.Smartphones have a number of features including speed, simplistic interface, integrated communications, which make them a valid alternative to a tradition desktop computer3Franko OI. Smartphone apps for orthopaedic surgeons. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011 Jul.;469(7):2042–2048. t. Tablet devices like the iPad (Apple Computer, Cupertino California) have been described as portable medical libraries4Berger E. The iPad: gadget or medical godsend? Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Mar. 1;56(1):A21–2..

Smartphone usage amongst doctors, and surgical trainees has previously been investigated5Franko OI, Tirrell TF. Smartphone App Use Among Medical Providers in ACGME Training Programs. J Med Syst. 2011 Nov. 4. , but the specific usage by orthopaedic surgeons in Australia has not been fully investigated.

These mobile devices provide several different functions for users. The most common of these are the ability to send and receive text, multimedia or picture messages; send and receive emails; browse the Internet and use specific applications (apps). These functions together or separately provide surgeons with additional tools to aid in clinical practice.

Some clinical applications of smartphone usage in orthopaedic surgery have previously been examined6Archbold H, Guha A, Shyamsundar S. The use of multi-media messaging in the referral of musculoskeletal limb injuries to a tertiary trauma unit using: a 1-month evaluation. Injury. 2005. ,7Elkaim M, Rogier A, Langlois J, Thevenin-Lemoine C, Abelin-Genevois K, Vialle R. Teleconsultation using multimedia messaging service for management plan in pediatric orthopaedics: a pilot study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010 Mar.;30(3):296–300. , and shown to have potential for timely and cost effective management of orthopaedic patients.

We sought to further delineate the usage patterns and preferences of mobile technology use amongst the orthopaedic profession in Australia.

Materials and Methods

Data collection for this study was performed via a survey of orthopaedic surgeons and registrars in Australia. An online, digital survey was developed to question participants regarding their level of training, smartphone and tablet ownership, current and future intended usage, and perceived impact on productivity and patient care. A free response section was included to allow respondents to add further comment to their experiences.

The survey was designed to be brief, and was planned in line with previously published recommendations to improve response rate amongst orthopaedic surgeons8Sprague S, Quigley L, Bhandari M. Survey design in orthopaedic surgery: getting surgeons to respond. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2009 May;91 Suppl 3:27–34. .

The survey was distributed by email, with an explanation provided regarding the purpose of the survey. In addition respondents were encouraged to forward the survey on to other orthopaedic surgeons and registrars. Completion of the survey acted as consent. All responses were anonymous, and data was kept securely.

Some basic demographic information surrounding age and level of training was collected. The respondents answered a number of questions regarding their current and possible future implementation of these devices, and the perceived impact on patient care and productivity.

Responses were collated and entered into a Microsoft Excel (2010) spreadsheet. Descriptive statistical analyses were then performed to ascertain percentage responses to each question.

Results

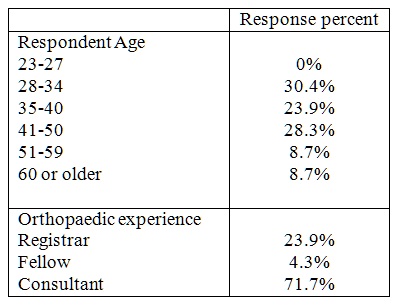

A total of 92 total responses were received, comprised 22 orthopaedic registrars, 4 orthopaedic fellows and 66 orthopaedic consultant surgeons. The majority of recipients were between the ages of 28 and 40 (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographics of respondents

Over 97% of respondents owned a smartphone, and 56% owned a portable tablet device. Of these, all but two used their devices regularly for work.

The main uses for mobile technology in clinical orthopaedic practice are for professional contact,i.e. with other doctors and surgeons (79%), and for accessing journal articles and other educational resources online (65.1%).

When the respondents were questioned on which specific features of mobile technology they would like to use in the future, the ability to view x-rays and other radiology imaging on their device was most desired (86%). A majority also intended or would like to view journals or online resources (65%), or use their device for practice management (63%) and the viewing and entering of medical records (63%).

Those answering the survey were asked about their use of text or multimedia messaging services (MMS) and email. Use of these modalities for professional contact (93% text/MMS; 86% email) was popular, as was sending and receiving clinical photographs and x-rays / radiology images (76%; 76%).

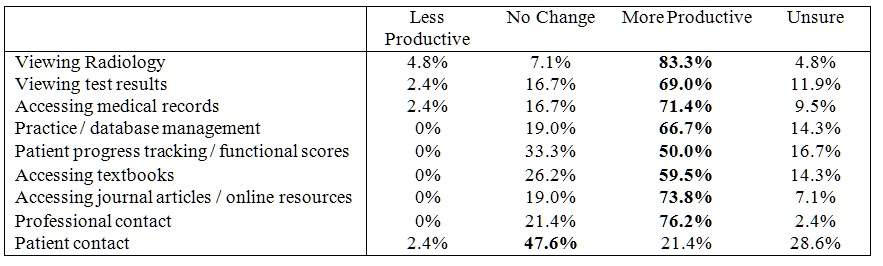

When questioned about how various facets of mobile technology impact on productivity, a large number of respondents indicated these technologies increased productivity (Table 2). Most respondents identified viewing patient investigations and accessing patient records as the most productive purpose for mobile phone use in orthopaedic practice.

Table2: The effect of accessing or using specific resources on productivity

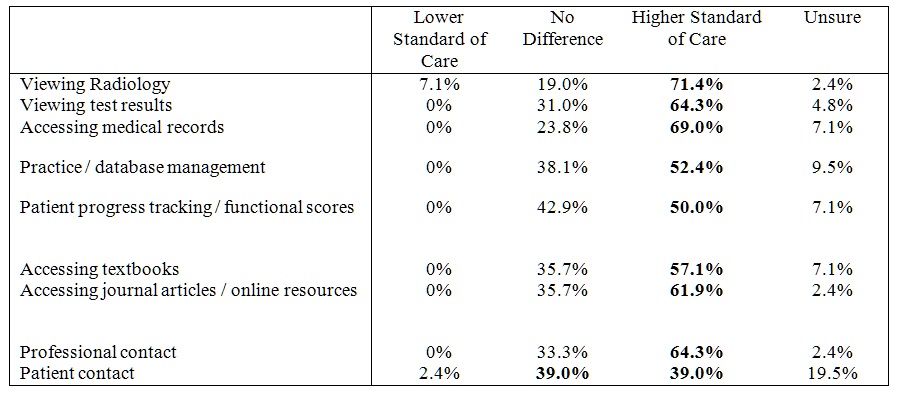

Table3: The effect of accessing or using specific resources on patient care

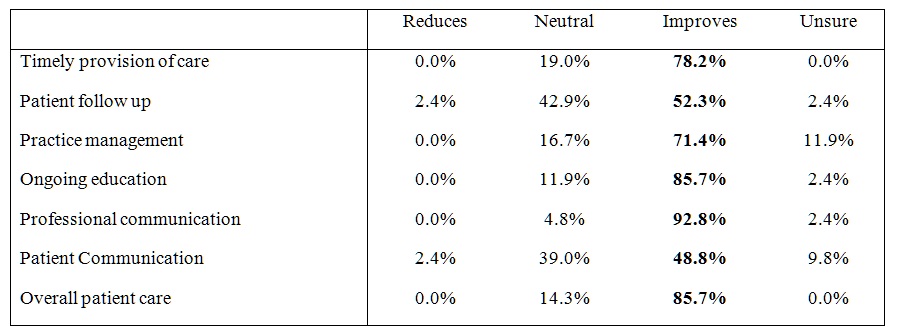

Table 4: Effect of mobile technology on different aspects of clinical orthopaedics

Additionally, when questioned about the effect of mobile technology on several areas of clinical orthopaedics, responses showed almost no perceived negative effects (Table4). The use of mobile phones for professional contact featured highly amongst orthopaedic trainees and surgeons, and 93% identified that mobile technology improved professional communication. Importantly, 86% believed that the effects of mobile technology in clinical practice would improve patient care.

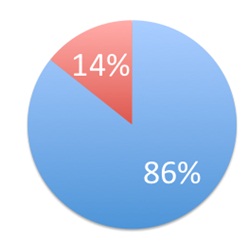

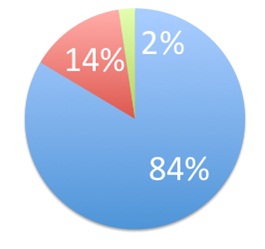

Overall most orthopaedic surgeons and registrars indicated that they were likely to use mobile technology more in the future (86%)(Figure 1). The majority also replied that overall mobile technology improves the level of patient care (83%).(Figure 2)

Figure 1 – “How do you see your own use of mobile technology in orthopaedics in the future, compared to your current use?”

Figure 1 – “How do you see your own use of mobile technology in orthopaedics in the future, compared to your current use?”

- I will use it more (86%)

- I will use it the same amount (14%)

Figure 2 – “What do you think is the overall effect of mobile technology on patient care in orthopaedics?”

Figure 2 – “What do you think is the overall effect of mobile technology on patient care in orthopaedics?”

- 83% – Improves level of care

- 14% – No Change

- 2% – Reduces Level of Care

Discussion

Smartphones and tablet devices have had a profound effect on the access and transmission of information, and their use is continually increasing.The medical world has often been at the forefront of the development and implementation of new technology. This study highlights the exceptionally high usage rates of these technologies by orthopaedic surgeons and registrars.

One interesting aspect is the wish to use apps to view radiology on smartphones and tablet devices. Currently there are no specific apps available in Australia that allow direct access to radiology picture archiving and communication systems (PACS). Currently the common implementation of offsite radiology is to use a Citrix based system to have access to the hospital computer network. However, Synapse (FujiFilm, Tokyo, Japan) has a mobile app available (Synapse Mobility) to connect to institutions running their Synapse PACS. At time of research, this app was not operational in Australia. Concern was raised by several respondents of the study about the resolution of screens and possible medico-legal issues arising from this. However respondents indicated that the ability to view imaging gave the ability to initiate timely treatment.

The survey results addressing the impact of mobile technology on productivity and the impact on patient care were almost universally positive. This provides an indication that the orthopaedic community see these devices as key to the timely provision of both clinical treatment and administrative duties, and their effect is positive both for the clinician and patient. It was interesting to note the only area that respondents felt mobile technology may not be helpful was in patient contact. This is understandable, as most clinicians prefer to interact in person with their patients.

The majority of orthopaedic surgeons and trainees foresee that the use of mobile technology will increase in orthopaedics. This presents a great opportunity for developers of apps for these devices to target the orthopaedic community. Previous research has shown that orthopaedic surgeons are highly willing to pay for high-quality apps3Franko OI. Smartphone apps for orthopaedic surgeons. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011 Jul.;469(7):2042–2048. .In addition to this, hospitals need to be cognizant of the increasing use of mobile technology by clinicians. A concerted effort should be made to integrate mobile technology into the existing systems available.

This study does have some limitations. It consisted of a novel, non-validated survey that was distributed to and amongst orthopaedic surgeons and trainees. The 92 responses received may not necessarily be representative of the 1,362 current members of the Australian Orthopaedic Association9Association AO. AOA Annual Report 2010-2011. aoa.org.au. cited 2012 Mar. 10. Available from: http://www.aoa.org.au/Libraries/AGMs/2011AnnualReport.sflb.ashx. By using a survey that was delivered by email, and completed digitally, bias may be introduced when surveying about technology. Future studies comparing the use of mobile phone technology amongst other subspecialties would provide interesting insights into the relevance of mobile-based applications across surgical and non-surgical specialties. This information could guide the use of more relevant applications for each specialty.

Conclusion

It is apparent from this study that use of smartphones and tablets in orthopaedics is already widespread in Australia. They are already an important tool for communication, professional development, productivity and patient care.Clinicians believe that their effect is positive on productivity and patient care, and that their use will increase in coming years.

Appendices

PDF of Survey: https://www.journalmtm.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/jmtm.12.appendix1.pdf

References

1. Petrovic D. Smartphone Usage in Australia [Internet]. Petrovic D. Smartphone Usage in Australia. [cited 2012 Mar. 20]. Available from: http://dejanseo.com.au/smartphone-usage-in-australia/

2. Moses A. Australia’s white hot smartphone revolution [Internet]. smh.com.au. 2011 [cited 2012 Mar. 12]. Available from: http://www.smh.com.au/digital-life/mobiles/australias-white-hot-smartphone-revolution-20110908-1jz3k.html

3. Franko OI. Smartphone apps for orthopaedic surgeons. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011 Jul.;469(7):2042–2048.

4. Berger E. The iPad: gadget or medical godsend? Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Mar. 1;56(1):A21–2.

5. Franko OI, Tirrell TF. Smartphone App Use Among Medical Providers in ACGME Training Programs. J Med Syst. 2011 Nov. 4. ![]()

6. Archbold H, Guha A, Shyamsundar S. The use of multi-media messaging in the referral of musculoskeletal limb injuries to a tertiary trauma unit using: a 1-month evaluation. Injury. 2005. ![]()

7. Elkaim M, Rogier A, Langlois J, Thevenin-Lemoine C, Abelin-Genevois K, Vialle R. Teleconsultation using multimedia messaging service for management plan in pediatric orthopaedics: a pilot study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010 Mar.;30(3):296–300.

8. Sprague S, Quigley L, Bhandari M. Survey design in orthopaedic surgery: getting surgeons to respond. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2009 May;91 Suppl 3:27–34.

9. Association AO. AOA Annual Report 2010-2011 [Internet]. aoa.org.au. [cited 2012 Mar. 10]. Available from: http://www.aoa.org.au/Libraries/AGMs/2011AnnualReport.sflb.ashx