Access and Preferences for Mobile Technology among Diverse Hepatitis C Patients: Implications for Expanding Treatment Care

Julie Beaulac1,2, Louise Balfour1,2, Kim Corace2, Mark Kaluzienski3, Curtis Cooper2,3,4

1Department of Psychology, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada;

2Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON;

3Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa;

4The Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa

Corresponding Author: jbeaulac@toh.on.ca

Journal MTM 8:1:11–19, 2019

Background: Mobile technology interventions present opportunities for enhanced patient engagement and outcomes.

Aims: To assess the feasibility and patient attitudes toward using mobile technology in HCV care.

Methods: Cross-sectional survey data were collected from HCV patients (N=115) at two sites, an academic hospital-based outpatient viral HCV program (n= 92) and a mostly low SES community-based site (n = 23). Measures included demographics, HCV disease status and risk factors, and mobile technology access and preferences. Differences in mobile technology access, use, and preferences by treatment site, treatment experience, ethnicity, gender, education level, and income level were assessed by Mann-Whitney and chi-square tests.

Results: 78% owned a mobile device. Of these, 69% reported having Internet access and 72% unlimited text plans. 66% reported comfort in texting. Half liked the idea of using a cell phone for HCV clinical care; others expressed dislike/uncertainty. Poorer access to mobile technology was reported by treatment naïve, community site, and non-White participants (p values ranging from 0.02 to 0.01). Respondents from the community rated lower comfort in texting (p = 0.01). A similar trend was noted for respondents with incomes below $30,000 as compared to higher income (p = 0.09). Yet, groups similarly liked the idea of using mobile technology in HCV care.

Conclusion: Mobile technology is an alternative model to augment existing HCV care. Variability in acceptability and accessibility of this approach was highlighted. Tailoring care delivery to individual patients with a particular focus on patients being served in community-based programs with low SES will be critical.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, Patient Engagement, Patient Attitudes, Cell Phones, Cross-Sectional Survey

Background

Compared to other common infectious diseases in Canada, chronic hepatitis C (HCV) is associated with high morbidity and mortality (1). Health related quality of life and productivity loss is diminished. Of the 110,000 Ontarians infected with HCV, 35,000 are unaware of their status (1–3). The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Program (TOHVHP) is the primary referral centre for Eastern Ontario, Canada providing interdisciplinary care to over 5000 patients with HCV. Canadians have access to publically-funded provincial health care. However, coverage for medication costs varies by provincial funding criteria and, in some cases, by private health benefits (4). Although successful in engaging many living with HCV, current TOHVHP initiatives face challenges in reaching all individuals with HCV in Eastern Ontario. HCV disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, who can be difficult to engage and retain in treatment due to issues related to mental illness, substance use, legal problems, social determinants of health (e.g., unstable housing, limited finances), discrimination and distrust, amongst other barriers (5, 6). Loss to follow-up remains a common problem. In this era of well tolerated and highly curative treatments, gaps in access directly result in individual harm via disease progression and threats to public health via viral spread. With expensive HCV treatments, suboptimal adherence can lead to costly treatment failures, viral resistance and transmission to other at risk individuals of refractory virus.

Innovative and integrative approaches of engaging HCV patients are needed in order to respond to the complexities of HCV care, including different treatment delivery methods. Approaches to help bridge the gap between HCV patients and treatment are particularly important. In addition to tertiary clinic hospital-based care, two innovative services within TOHVHP seek to reach patients who might not otherwise access hospital-based clinics: (a) a Telemedicine Program (TM) and (b) a Community Liaison Patient Support Program (CLP). These services include dedicated staff that facilitate the linkage of patients to services, and in the case of TM, offer “real-time” HCV specialist visits to increase access to care in underserviced communities (e.g. rural communities, marginalized populations) (7–10). These programs have been valuable in providing HCV care to a population facing individual and systemic barriers to accessing traditional models of hospital based care. The TM and CLP programs are integrated innovations but limited by expensive clinician hours. Given Ontario’s 110 000 HCV infected patients, novel strategies will be needed to expand expert care in a cost effective manner. Mobile interventions represent another approach to engaging this population into care with the further possibility of enhancing care during treatment. Mobile technology could provide information and support in a format that is often more accessible and less resource intensive (11). Research has highlighted limited HCV knowledge among HCV patients (12) and the particular need for new and more accessible delivery of HCV educational information and support to marginalized individuals living with HCV (13).

Mobile technology interventions present opportunities for patient self-monitoring, intervention, and facilitating contact and engagement between patients and health care providers. A growing body of research demonstrates the value of mobile applications for enhancing patient engagement, retention, satisfaction, and health outcomes (10, 14–18). This technology has been evaluated in HIV populations in both higher (15) and lower-income regions (10). Important lessons learned from this ground breaking work include 1) most people have cell phones and are willing to consider mobile device use for communication with healthcare team members; 2) the technology can be consistently and confidentiality maintained; 3) high frequency messaging has little additional impact on improving outcomes compared to once weekly messages; and, 4) supportive / caring messages are more effective than simple reminder messages or messages that provide instruction. In the context of HIV, evidence suggests that mobile technology adherence applications can be used to make people feel cared for which in turn improves measurable clinical outcomes. Research has supported the use of mobile technology for augmenting health services in the context of lower income and marginalized populations (e.g., HIV and medication adherence) (19). This mobile application has also been assessed in tuberculosis with similar positive outcomes but has yet to be investigated in the HCV population. (16)

Study Objectives

We aimed to lay the ground work for implementation and evaluation of a cell phone based application seeking to increase patient engagement and retention in care, improve treatment adherence and completion, and ultimately increase successful HCV treatment delivery. A convenience sample survey conducted at The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Program (TOHVHP) from August to October 2015 determined that over 90% of TOHVHP clinic patients own a cell phone (20). We report on our formative evaluation, which systematically assessed feasibility and patient attitudes toward using mobile technology in HCV care.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among HCV patients with The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Program (TOHVHP) including the hospital site and a Community Liaison Program community partner site. Participants from the hospital site were approached between March and December 2016 as they waited for an appointment, many completing the survey at that same time, while participants from the community site completed the survey during a December 2016 drop-in clinic breakfast. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were over the age of 18 years, had a current or past diagnosis of HCV and were able to complete the survey in English. Pre-, peri- and post-HCV antiviral treated patients were included. Participants received $10 for survey completion. The study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (REB #2015-0909) and all participants completed a consent form.

The survey included questions on demographics (e.g., age, ethnicity, level of education, adapted from questions used by the Centre for Addiction & Mental Health), HCV disease status and risk factors (e.g., time since diagnosis, previous treatment experience), and mobile technology use. Mobile technology questions assessed feasibility (e.g., access to devices) as well as patient opinions and preferences regarding communication via cell phone texts and e-mails. This portion of the survey was adapted from questions validated in the HIV population and included 19 items (17). For instance, participants were asked to rate how comfortable they were using a cell phone to send and then to receive text messages along a 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 5=extremely). They were also asked open-ended questions such as what they would want text messages to say if they were able to receive these from their health care provider, and what they would want to tell or ask of their providers by text. Administrative data was also utilized from a clinic database for patients followed at TOHVHP (REB 2004-196), including demographic and health information (e.g., HCV disease status, HCV treatment history). This information supplemented data collected through survey format.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 24 was used for statistical analyses. Data were prepared for analysis (20% of data verified for accuracy, all data checked for outliers and discrepancies) and missing values were not imputed. Standard descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the participants and their access to and attitudes toward using mobile technology in HCV care. Qualitative responses to open-ended questions regarding preferences and concerns about using mobile technology in HCV care were compiled and summarized. Mann-Whitney tests were used to assess for differences in reported comfort with mobile technology use in HCV care (ordinal dependent variable) between patient groups. Chi-square tests were used to assess for differences in mobile technology access, use, and preferences (nominal dependent variables) by categorical independent variables (treatment experienced vs. naïve; gender – male vs. female; ethnicity – White vs. other; site – hospital vs. community; education – completed high school vs. less than high school; income: up to $29,999 vs. $30,000 or more). No formal sample size calculation was conducted. Our aim was to complete questionnaires with at least 100 participants which we predicted would allow for robust descriptive and comparative analysis.

Results

Of 165 participants approached across hospital and community sites, 140 (85%) agreed to participate. Of the 140, 115 completed and returned the survey, (23/24 for the community site, 92/117 for the hospital site; 82%). Participants declining to participate commonly cited the following reasons: no time, not being interested, or not being able to read or speak English.

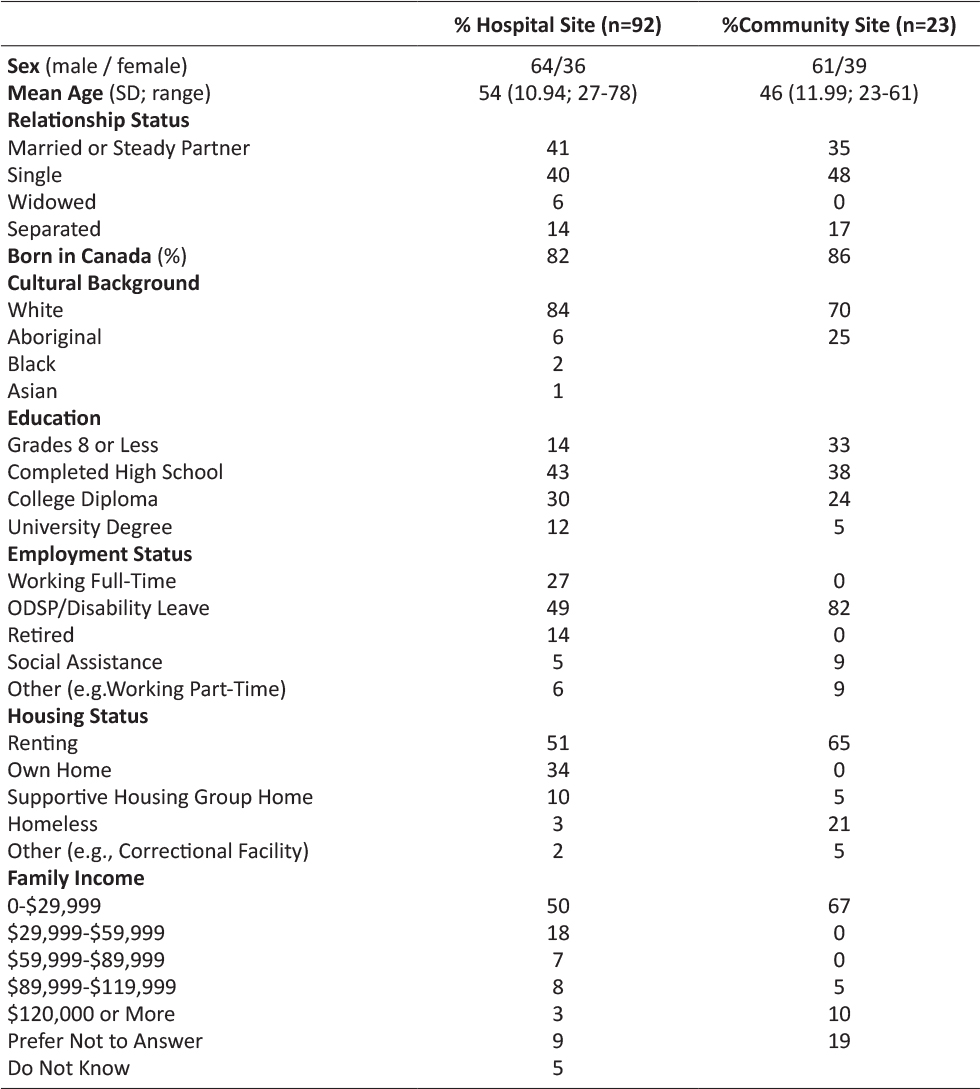

Survey participants (N=115) had a mean age of 52 years (range 23 to 78), 64% were male and 82% White. Half of participants (49%) were on the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) or Disability Leave and 60% reported high school education or less. Table 1 provides further information on the demographic characteristics of survey participants by site.

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Participants

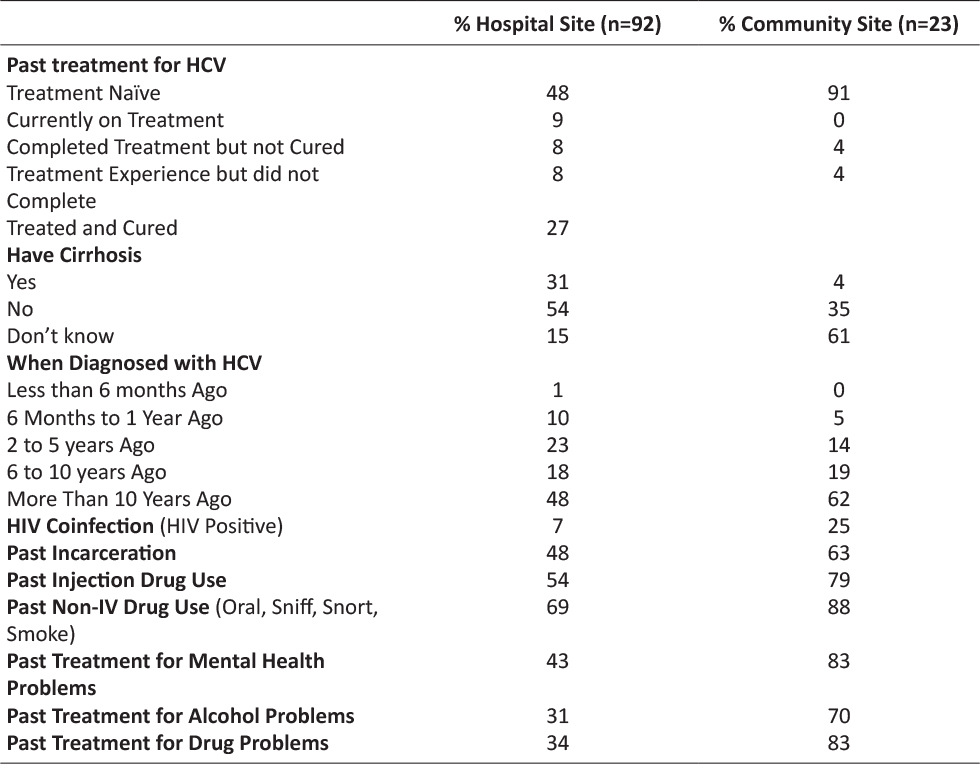

In terms of the health characteristics of the sample, almost all participants were diagnosed with HCV two or more years prior and most were HCV antiviral treatment naïve. The majority reported past incarceration, injection and/or oral drug use, and past treatment for mental health, alcohol, and/or drug use (Table 2).

Table 2: Health Characteristics of Participants

Mobile Technology Access and Preferences

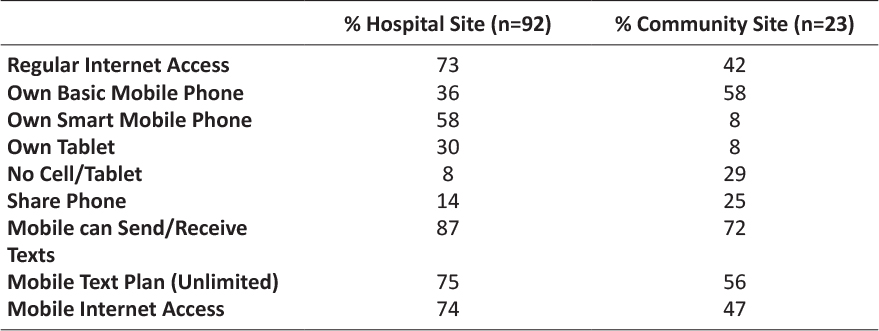

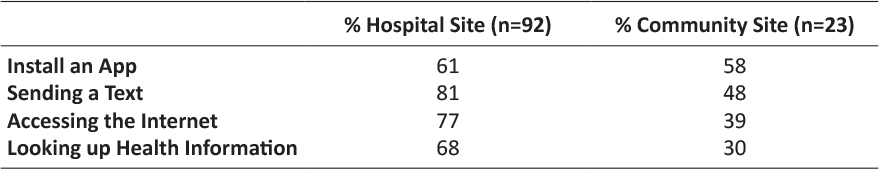

Most reported having regular access to mobile technology. 92% of hospital site participants and 71% of community site participants reported owning a mobile device (cell or tablet); most of these mobile devices had access to the Internet (74% for hospital site and 47% for community site), could send/receive texts (87% vs. 72%) and were set up with unlimited text plans (75 % vs. 56%). Most reported sending/receiving on average 1-10 or 10-100 texts per week from their mobile devices (37% and 37%, respectively for hospital site vs. 33% and 22%, for community site). Similarly, most reported sending/receiving about the same amount of emails (28% and 42% for 1-10 and 10-100, respectively for hospital site and 43% and 36% for 0 and 1-10, for community site). Fewer reported using non-mobile technology: 46% (hospital site) and 8% (community site) indicating that they owned a landline phone and 56% (hospital site) and 26% (community site) reporting regular use of a desktop computer (see Table 3 for more details on mobile technology access). In terms of experience with mobile technology, the majority reported having used mobile devices to install an app, send a text, access the Internet, and/or look up health information (Table 4). Fewer community site participants reported such use.

Table 3: Mobile Technology Access

Table 4: Experience with Mobile Devices

Although most indicated that they had never used mobile technology to communicate with a health care provider, 21% of community site participants and 14 % of hospital site participants reported email correspondence and 17% of community site participants and 16% of hospital site participants indicated interaction by text. According to the survey responses, the contact was initiated by the health care provider (44% of cases for community site, 20% of cases for hospital site), the patient (31% for community site, 32% of cases for hospital site), or both patient and provider (25% for community site, 48% of cases for hospital site). When asked who they would prefer to contact them by text or email for health advice, the highest rated health care providers were the physician (42% for community site, 32% for hospital site) and nurse (21% for community site, 22% for hospital site). No preference was indicated by 32% of community site and 30% of hospital site of participants.

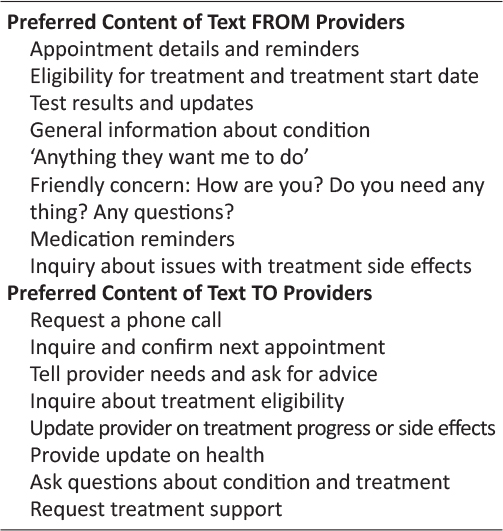

Comfort in texting varied by site (see Table 5). When asked directly if they liked the idea of using a cell phone for HCV clinical care and follow-up, 61% of community site participants and 49% of hospital site participants reported affirmatively, citing reasons including ease, efficiency, convenience, and speed. In contrast 22% of community site participants and 34% of hospital site participants reported that they would not like using cell phones, identifying concerns related to cell/network access issues, the impersonal nature of method, a preference for in-person or other method of communication, concerns about texting being too slow to receive answers to their questions, and language and/or technology literacy issues. Some (17% of community site and 17%) also reported uncertainty, indicating that they would need to try this method before deciding. Many participants shared ideas for text content should they be able to communicate with their health care provider by text (Table 6). Key patient concerns related to HCV care and texting included privacy issues and losing meaning of information in exchange.

Table 5: Comfort Texting

Table 6: Content Preferences of Texts for HCV Care

Group Differences Related to Mobile Technology Use in HCV Care

Access to mobile technology significantly differed by past HCV antiviral treatment exposure, ethnicity, and site. Treatment naïve (36/63; 57%) and community site participants (10/24; 42%) were significantly less likely to report access to the Internet (p=0.02 and p=0.01, respectively), as compared to treatment experienced (40/51; 78%) and hospital site participants (66/90; 73%); and to not owning a mobile device (cell or tablet; 12/63; 19% treatment naïve vs. 2/50; 0.04% treatment experienced; p=0.02 and 7/24; 29% community site vs. 7/89; 0.08% hospital site participants; p=0.01, respectively). White respondents (71/85; 84%) were less likely to report owning a mobile device (p=0.02) as compared to non-White participants (28/28; 100%); However, internet access, did not differ by race. Access to mobile technology did not differ by gender, education level, or income level. There were no differences in past experience communicating by text or email with a health care provider by gender, ethnicity, treatment experience, site, education level, or income category. There were no differences in reported liking of the idea of using mobile technology in HCV care between any groups (i.e., no differences by gender, ethnicity, treatment experience, site, education level, or income category).

Mann-Whitney tests indicated that reported comfort with sending texts, comfort with receiving texts, and comfort sending/receiving texts in English did not differ by gender, ethnicity, treatment experience, level of education, or income. However, respondents with income of under $30,000 trended toward lower reported comfort in sending/receiving texts in English (p = 0.09). Respondents from the community site rated significantly lower levels of comfort across all the three variables (p = 0.04, p = 0.04, and p = 0.01, respectively).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and patient attitudes toward using mobile technology in HCV care. Our findings suggest that mobile technology may be an attractive and feasible alternative modality to augment existing HCV care. Consistent with past research (e.g., 18), most participants reported owning a mobile device (basic cell, smart phone, or tablet) and of these, the majority also reported having access to the Internet and to having unlimited texting plans on their devices. Although past experience using mobile technology in their care was limited, the majority reported comfort in sending/receiving texts, and half of respondents liked the idea of using a cell phone for HCV clinical care and follow-up. It was noted that the other half reported not liking this idea or uncertainty about using this modality in their care. Given this, further work is necessary to understand the reasons for this reluctance. HCV stigma may be a factor leading some to fear breaches in privacy/confidentiality when using mobile technologies for HCV care. Strategies to increase patient ease with mobile communication may be necessary. There were no differences between respondents from the hospital outpatient setting and the community-based clinic in reported liking of the idea of using mobile technology in HCV care. However, access to mobile technology differed across some groups as did rated comfort in texting. This variability underscores the heterogeneous nature of the HCV patient population and highlights the need in tailoring delivery of care to specific patient needs and preferences in order to effectively engage all individuals with HCV. There is no one standard practice for engaging patients in HCV care.

The finding that access to mobile technology differed by treatment experience is interesting. Treatment naïve patients were less likely to report access to the internet and mobile technology; this may suggest a general tendency for patients not previously engaged in treatment to also be less connected to technology and other communication/information systems that could inform them of their treatment options. The finding that access to technology was lower among community site participants was not surprising given the marginalized and lower-income nature of this population. This group was also less comfortable in communicating medical issues by text. This may be due to reduced trust in health care providers or over all less experience in day-to-day use of texts to communicate. Notwithstanding this finding, mobile technology interventions have been shown to positively impact health outcomes in other marginalized and lower-income populations. Given this population is an explicitly targeted priority population for HCV treatment engagement in the province of Ontario (2) and elsewhere, understanding the particular needs and interests of this group will be critical to fully understand and consider as mobile technology-based HCV treatment programs evolve.

The population captured in this study had high rates of substance use, history of mental health difficulties, and incarceration. The rate of incarceration in Canada (115 per 100 000) is much lower than the 51% reported in our sample patients with HCV. We know that HCV rates are high among prisoners (21). There are a number of reasons that have been cited in the literature for the high HCV infection rate in prisons including high rates of substance users, risk of infection while sharing needs, razors, and other materials, and testing programs within institutions. It is also worth noting that Canada has a lower incarceration rate (115 persons in custody per 100,000 population) as compared to the United States which has 666 persons in custody per 100 000. (22)

Limitations and Strengths

Study limitations included the generalizability of findings as the sample surveyed consisted of patients primarily from a tertiary care center based in an urban Canadian setting. However, it is important to note that our Community Liaison Program is very effective in engaging and retaining community-based HCV patients in care within our hospital-based clinic. The inclusion of patients from a community partner clinic, relatively large sample size, high participation rate, and the broadly representativeness of the sample, enhances the generalizability of our findings. Patients completed the surveys autonomously and separate from health care providers, which limit any influence of factors including social desirability bias. To further verify representation of diverse patient groups including those not engaged in hospital-based HCV care, future research drawing from community samples is warranted, with particular attention to patients with low literacy levels and/or who speak languages other than English.

Conclusion

As health care providers attempt to improve patient engagement and experience of care while at the same time reduce health care costs, teams are seeking to adopt innovative, integrated, community-oriented models of care delivery. Mobile applications may represent a useful tool for augmenting engagement, retention and successful HCV treatment among many different groups.

For instance, while higher income individuals may be interested in using mobile technology as a way of minimizing their clinic visits, such technology may provide the necessary bridge to connecting lower income individuals with HCV care. This study provides support for trialing mobile innovations in HCV care. Potential engagement obstacles as well as individual patient needs and preferences should be fully understood in an effort to provide optimal care.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Richard Lester for providing access to survey questionnaires and approval to modify for use in our work.

Disclosures

Curtis Cooper – Speaker/Advisor/Research Funds: Gilead, Merck, Abbvie

Kim Corace- Speaker Fees: Janssen, Vertex, AbbVie, Novo Nordisk

Mark Kaluzienski – Lundbeck, Sunovion, Otsuka

The following people have nothing to disclose: Julie Beaulac, Louise Balfour.

References

1. Kwong JC, Ratnasingham S, Campitelli MA, Daneman N, Deeks SL, Manuel DG, et al. The impact of infection on population health: results of the Ontario burden of infectious diseases study. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44103. ![]()

2. Ontario Hepatitis C Task Force. A Proposed Strategy to Address Hepatitis C in Ontario 2009-2014 [PDF]. Toronto: The Government of Ontario 2009 [Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/hepatitis/docs/hepc_strategy.pdf.

3. Remis R. Modelling the Incidence and Prevelance of Hepatitis C Infection and Its Sequelae in Canada, 2007 [Online Multimedia]. 2007 [Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/sti-its-surv-epi/model/pdf/model07-eng.pdf.

4. Marshall AD, Saeed S, Barrett L, Cooper CL, Treloar C, Bruneau J, et al. Restrictions for reimbursement of direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in Canada: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(4):E605-E14. ![]()

5. Myers RP, Shah H, Burak KW, Cooper C, Feld JJ. An update on the management of chronic hepatitis C: 2015 Consensus guidelines from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29(1):19-34. ![]()

6. Treloar C, Rance J, Backmund M. Understanding barriers to hepatitis C virus care and stigmatization from a social perspective. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57 Suppl 2:S51-5. ![]()

7. 2013 Canadian Telehealth Report. 2013 Canadian Telehealth Report [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://www.coachorg.com/en/resourcecentre/resources/TeleHealth-Public-FINAL-web-040413-secured.pdf.

8. Telehealth [Online Multimedia]. 2015 [Available from: https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/index.php/programs-services/investment-programs/telehealth.

9. Parmar P, Mackie D, Varghese S, Cooper C. Use of telemedicine technologies in the management of infectious diseases: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(7):1084-94.

10. Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838-45. ![]()

11. Mental Health Commission of Canada. E-Mental Health in Canada: Transforming the Mental Health System Using Technology Ottawa, ON2014 [Available from: http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca.

12. Balfour L, Kowal J, Corace KM, Tasca GA, Krysanski V, Cooper CL, et al. Increasing public awareness about hepatitis C: development and validation of the brief hepatitis C knowledge scale. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23(4):801-8. ![]()

13. Treloar C, Jackson C, Gray R, Newland J, Wilson H, Saunders V, et al. Care and treatment of hepatitis C among Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia: implications for the implementation of new treatments. Ethn Health. 2016;21(1):39-57. ![]()

14. Murray MC, O’Shaughnessy S, Smillie K, Van Borek N, Graham R, Maan EJ, et al. Health Care Providers’ Perspectives on a Weekly Text-Messaging Intervention to Engage HIV-Positive Persons in Care (WelTel BC1). AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1875-87. ![]()

15. Smillie K, Van Borek N, Abaki J, Pick N, Maan EJ, Friesen K, et al. A qualitative study investigating the use of a mobile phone short message service designed to improve HIV adherence and retention in care in Canada (WelTel BC1). J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(6):614-25. ![]()

16. van der Kop ML, Memetovic J, Patel A, Marra F, Sadatsafavi M, Hajek J, et al. The effect of weekly text-message communication on treatment completion among patients with latent tuberculosis infection: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (WelTel LTBI). BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004362. ![]()

17. Lester RT. Ask, don’t tell – mobile phones to improve HIV care. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1867-8. ![]()

18. Ershad Sarabi R, Sadoughi F, Jamshidi Orak R, Bahaadinbeigy K. The Effectiveness of Mobile Phone Text Messaging in Improving Medication Adherence for Patients with Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(5):e25183. ![]()

19. Miller CW, Himelhoch S. Acceptability of Mobile Phone Technology for Medication Adherence Interventions among HIV-Positive Patients at an Urban Clinic. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013:670525. ![]()

20. Beaulac J, Corace KM, Balfour L, Kaluzienski M, Cooper C. Hepatitis C Patient Communication Source and Modality Preferences in the Direct Acting Antiviral Era. Manuscript (In Press). Manuscript submitted to the Canadian Liver Journal. 2018. ![]()

21. Zampino R, Coppola N, Sagnelli C, Di Caprio G, Sagnelli E. Hepatitis C virus infection and prisoners: Epidemiology, outcome and treatment. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(21):2323-30. ![]()

22. Reitano J. Adult correctional statistics in Canada, 2015/2016 [WebPage]. Statistics Canada; 2017 [updated March 1, 2017. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14700-eng.htm.